Using the example of how the American managed healthcare industry works, with its tendency to over-emphasize data tracking and documentation, I identified three risks in such a system:

- Inadequate Accounting of Costs, such that providers of healthcare services might go unpaid.

- Mis-Tracking of Interventions to Outcomes, possibly resulting in unnecessary procedures being performed on patients (or necessary procedures not being performed.)

- Confusion Leading to Avoidance, where the system as a whole becomes so daunting, patients avoid it until it's impossible to do so.

There are far from the only risks existing in the system, but are a few that came to mind for me. (Share yours, please?)

So, as promised, I'm digging in a little more deeply to look at the probability of these risks.

Inadequate Accounting

Setting aside for the moment one's particular view as to whether or not it should be so, the fact remains that healthcare in America is largely, if not predominantly, a for-profit enterprise.

Americans, on average, spent about $13,000/year (in 2022) on medical expenses1. That number varies widely across income brackets and ages, of course but... it's a lot of money. In total, American's spent $4.5 trillion on Healthcare. Combined, about half of that went to Physician and Clinical Services (20%) and Hospital Care (30%)2, so overall we can say that a very large amount of money was spent on delivering direct care to patients.

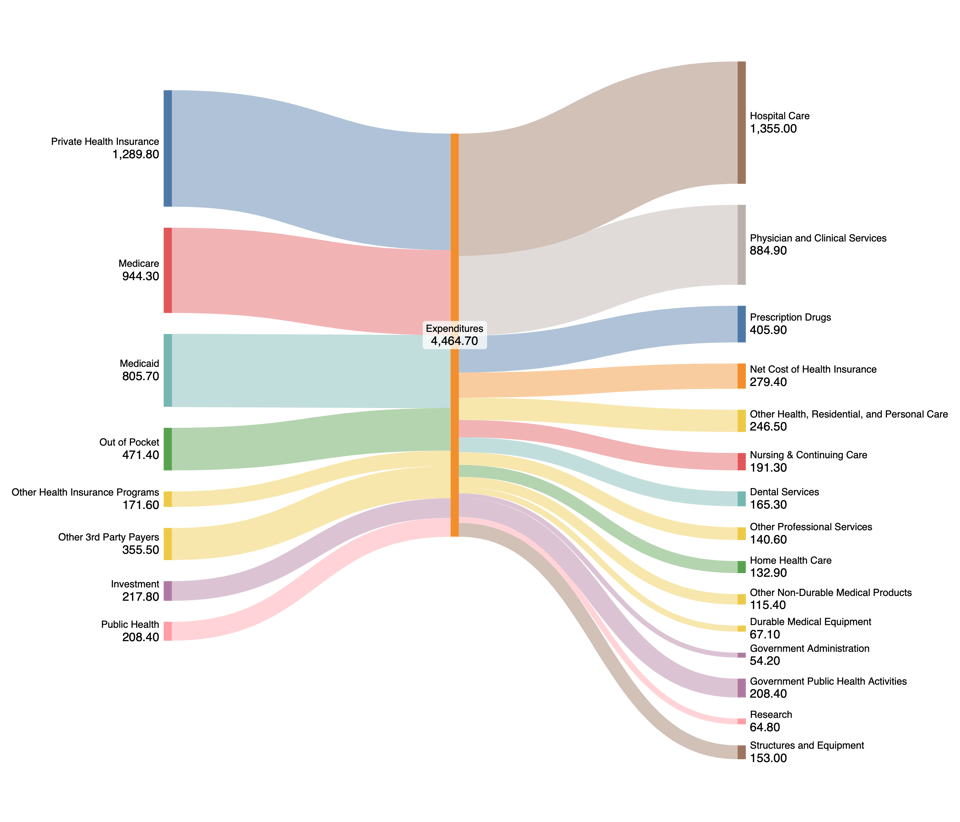

Who's paying? Mostly the Federal government (39%), Private Insurance companies (29%) and Individuals (11%). Generally speaking most of this money originates with individuals (through taxes or employer-sponsored healthcare plans; you can argue with me on whether or not those dollars would have ended up in people's pockets instead.) But leaving that aside, the "flow of funds" looks something like this:

A "flow" of healthcare expenses in the US in 2022. All numbers are in Billions (with a "B"). Total "sources" and "expenses" might not match because of rounding. You can click the link to download a .zip file of all the source data.

In those tendrils lay much opportunity for... complexity, errors, fraud, and misdirection.

But before we get to "WFA" (Waste, Fraud and Abuse), let's look at that diagram. Check out the fourth-highest line item:

Net Cost of Health Insurance: $279 Billion

About 6.3% of all healthcare spending goes to paying for insurance companies to do what they do net of all the money they pay for actual healthcare services: advertising, administrative expenses, sales costs, profits, etc. One way to think about that is to ask, "is it worth ~$300 billion to make sure everyone gets paid what they're owed?" Since most of what an insurance company does is take money from people, hold on to it for a while, and then pay it out again.

(The rough, baseline expectation for an insurance company is that it will take in, say, $100 in premiums and then - at some future point - pay out $100 in expenses. But in the meantime they get to hold on to the money and invest it - within certain limits. In essence, they "borrow" $100 from policy holders, invest that money in stocks and bonds for instance, and then pay the $100 out when the policy holder gets sick and needs to see a doctor. And if they earn $5 in interest on that "float", the insurance company gets to keep it. Some insurance companies pay out less than $100 for every $100 in premiums they collect, and some pay out more. And while it might be tempting to pay out nothing, this tends to put insurance companies out of business quickly - because who wants to pay premiums for a product that doesn't provide actual coverage. And, also, there are some Federal laws about how much of that $100 an insurance company has to pay out each year; otherwise they need to give the "excess" back to policy holders.)

You can quibble with that rough summary - there are certainly cost-containment things that insurance companies do to make sure people don't get "unnecessary" treatments, and they act as proxy negotiators for policyholders to help "keep costs down". One area where I won't get into, but will mention, is that having private companies do this is a policy choice. Government programs like Medicare and Medicaid do a lot of the same negotiating, though somewhat hamstrung by rules that prevent them from doing that for all but 10 specific prescription drugs3.

So: as a matter of risk mitigation, is paying (many) private companies worth it? What would happen if private health insurance went away... tomorrow (i.e., if "Medicare for All" were suddenly in force)?

Not much. Medicare and Medicaid spend 8% and 12%, respectively, on Administrative and Net Cost of Insurance. Private Health Insurers - as a group, I imagine there is some variation among insurers, though not much since by law (I alluded to this above) they must disperse 80% of their collected premiums each year - spend about 10%, and on a dollar-for-dollar basis, the government runs the same basic programs somewhat more expensively ($167 Billion vs. $131 Billion.) I suppose depending on your political leanings, you could argue this either way: but I think the basic message is that managing the intake and payout of dollars for health products and services is not so terribly prone to huge variation between private and government-run entities.

A slightly different, but important, question is: what would be the risk of not managing this at all, or managing it very poorly (whether privately or as a government agency)?

And for that, we have to talk about n'er-do-wells: Waste, Fraud, and Abuse.

Liked This? Subscribe: